Poet of Poland, your faith had you sterilised,

though you didn’t always wear its sheath.

What you took for inhuman things, whilst the fruiting flesh

rotted in your mind, demonic things, were things more solid

than your optimism, which fell with you into the grave.

I ask you which one was right? Mercy and salvation, the apple trees

of happy shade, have not visited the world since you died

and Robin’s fore-prophecy of love for the earth was more prescient

than your devoted superstitions. Vast white steaks of ice caps are melting.

Deforestation spreads like a cancer. Lips dyed with wine have not tasted

the rising sea levels. Monstrances fell like rotten sunflowers.

Your creed was mortal, Robinson’s immortal.

The earth teaches now that the eye of Carmel soared

and foresaw the catastrophes your Western trinkets wrought.

Tragedy spares us nothing. Reality spares even less,

not even the crosses and rosaries you squeezed.

Two Poems: Mother in Pau and Consolations in a Minor Key

Note: The first poem was written when my mother was in hospital (in Pau, Southwest France) for spinal surgery. The second was written after visiting Quarr Abbey monastery, where I saw pears growing, just as I remember from years ago. On the same day I saw wild plums growing on Cowleaze Hill, between Shanklin and Bonchurch.

MOTHER IN PAU, 14th JULY

Pyrenees and grape-blossom hills of Jurançon

you see from a window in the Clinic Navarre.

Feed the grapes with your sorrowing eyes: they will reward

the night with a pale flow of gold, a blaze of blue shade;

on your suffering shedding its hurt, a new lease of life.

Mother I miss you, and Boris’s Britannia a boat on the waves

of infantile worship, stupidity and betrayal.

Today I bless the French Republic: home of Danton, Celan, and Samuel Beckett:

the red wine rains will cure a sky that suffers

and gives you back to us renewed for the journey.

CONSOLATIONS IN A MINOR KEY

At Quarr I see the ordered weave, a trellis woven with pears.

Old friend, from autumn’s bronze to fruits of summer flame.

The plum’s wild purple curves beside the road on Cowleaze Hill.

Adorning sadness with colour, things pass in shape and sound

even where friendship leaves no visible trace.

New lights in fire-forms burst the shattering gloom:

I have lived too long, if still I live at the age of thirty-one.

Consolations come, a fruitful minor key, a trellis woven with pears.

Questions for the Whites

QUESTIONS FOR THE WHITES

How many white people really know?

How many white people really care?

Are they a small part of a larger mosaic?

Why have they gone for the jugular of diverse colours and tongues?

Do they hold nothing sacred but money and private property?

Why do they think only whites have made music, art, and literature?

Why do their children believe them? Praised be the ones that don’t!

Why do they gaze in the mirror of genocide, liking what they see?

Why have they used a middle-eastern Jew to justify criminal forms of whiteness?

Have few understood the values of Jesus? Have even fewer practiced them?

Do sacred intimations shine through to everyone?

Why have they not outgrown blood-sacrifice?

Why do they demand it only when blood doesn’t run white?

Why have they gored sundown-flowers with ink, ink of black lilies

denied tonight?

Why do they seek a refuge in pallid contempt for life?

Why do I hear a posh Englishwoman using the multi-ethnic Roman Empire as an excuse for postmodern white supremacy?

Why did Elizabethan Englishmen call their rage and contempt civilising?

Why did the Dutch carry more than thirty-one thousand Africans to New Holland for their lucrative labour in the sugar plantations? Why did the Dutch prostration before profits, and the English addiction of dehumanising via systems, devour so many?

Why did north European culture associate blackness with sinister treachery?

Why won’t Catholics take off their colonial robes?

Why did Protestants leave untouched the bone-structures of medieval fascisms?

Why did Puritans think the God of Christ a vicious white supremacist?

Why in 1541 was there only one surviving Guanche in the Canary Islands, permanently drunk?

Why did France nearly exterminate the Fox Indians, and why did they massacre two-thirds of Algeria’s natives?

Why was the wealth created in Bordeaux and Nantes, the grim wealth of slave-traders, the basis of bourgeois independence, the engine creating in the French Revolution?

Why did the US wage one of the bloodiest colonial wars against the Philippines?

Why do they build a walled garden with the skulls of Africa’s freedom?

Why did none of them question the slave trade before the eighteenth-century Quakers?

Why did they listen to Darwin when he theorised a white eclipse? And why did his “science” shrug its shoulders at genocide?

Why did they call the famine-riddled Irish nothing less than ‘white chimpanzees’?

Why did the Germans deploy genocide against the Herero people of south-west Africa? Why did they herd the battered remnants into concentration camps and reservations?

Why did they not learn from Gandhi when he said that Hitler was Britain’s sin?

Why in Australia did they say that Moorundie wasn’t inhabited, though the Ngayawang people have lived there for at least five thousand years?

Why does word processor not process their names?

Why in Tennant Creek are aborigines poisoned with alcohol?

Why did Spain ban the speech of one of the few pre Indo-European languages in Euskadi?

Why did the Scots fight for Anglo-Saxon ideology in India, Belfast, and Africa?

Are the Welsh aware of what their acquiescence has been used for?

Why does their education not teach them Toussaint and Baldwin?

Why did their feminists not weep for women in Bosnia?

Why do Catholic women agree to the false majesty of misogyny?

Instead of loving their neighbour, why do they garrotte them on borders drawn in sand?

Why do they not try to repair the damage done by their empires?

Why is hatred a strand in their DNA?

Botanic Psalm

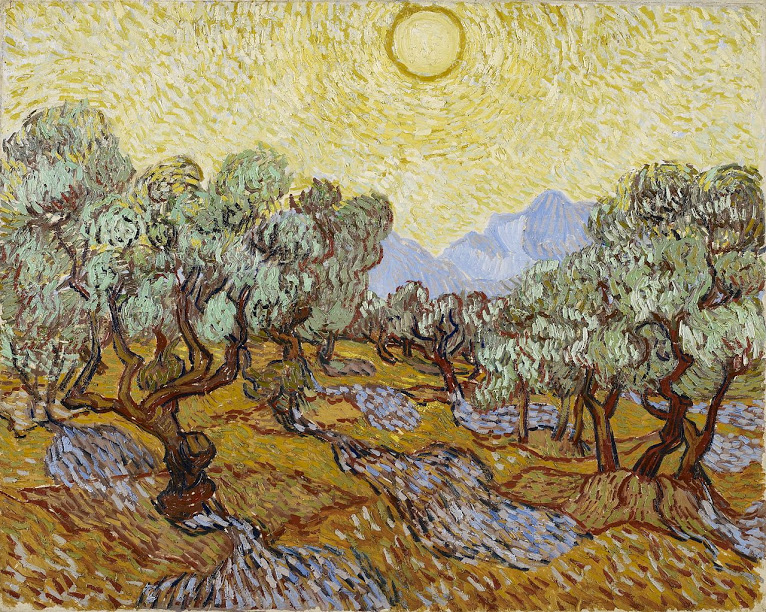

(Excerpt from a forthcoming collection of poetry celebrating the Spring beauty of the south-eastern Isle of Wight[1]. It was written among olive trees.)

The soil is dry

and leaves glass-tint

the olives, unborn

in May sun.

The scent of clementine

in the birdsong’s spark.

The citrus sun,

in silver-crimson

shoals of wine-blossom,

bled in the air.

Manes of purled olive-psalms

sing from the roots.

Gold-silent embers

in the air’s warm hands;

the owl’s spring is born

in honey-fur and light.

The vine waits

for feather-fruits

to heal a grieving child.

The light-fawn sun

gives the kiss of peace

as I wait for the page’s magnolia leaf.

The olive-wine syllable

is sweet, and the wedding at Cana

repeats: the magpie’s calligraphy

in the rosé leaves.

Oil-light loaves

distilled into Time;

take this and eat:

partaking of rhyme

no one mourns the robin

with leaves as dark as wine.

Sun-studded earth

is white wine for the eye –

how long will you be here

in poinsettia cries.

The silver-seraph plume

ablaze in shadow

with chalice-cream palms

cupped for Poiesis.

[1] https://www.countypress.co.uk/news/18371683.isle-wight-creatives-pulling-together-keep-people-entertained/

Reflections on Art and Poetry

My reflections here are arranged in three parts: (1) a personal response to seeing Seamus Finnegan’s I AM OF IRELAND directed by Ken McClymont and staged at The Old Red Lion Theatre in London; (2) a set of abstract reflections on the nature of art; and (3) a personal statement of my own view.

RESPONSE TO I AM OF IRELAND

Wherever there is art there is violence. It is the bellicose tenderness of the creative sensibility. It is part of the Lamb’s war against the forces of commodification, amnesia, secularism, meaninglessness, and mortality. A dark Light of the soul invading and annihilating assumptions, reason, and social layers. Pricking the conscience with questions: what is a nation? What has become of the mosaic of Irishness? What things hunt and haunt individuals and memories? What of the nightmare of Anglo-Irish relations? Can antagonism between present and future ever be dissolved? The coercions and perversions of thoughtless language are attacked by the scorched earth poetry of an anointing space – this is the experience of seeing I AM OF IRELAND. It is a Mass of remembrance, a sacrament uncontaminated by the world outside and the temptation of easy answers. It is as if Georg Büchner and Tadeusz Kantor spent decades in Ireland and I AM OF IRELAND was the result. The cast gnaw at the state of the nation, at the state of its consciences, and at the barrenness of early Twenty-First Century logic. The “smug arrogant careerist professors of ‘Irish Studies’” would do well to meet their eye. The cast also exposes the wounded polyphony of memory, voice, and sacrifice. Carving them onto the eye through expert handling of staging, gesture, and vignettes. The presence of the cross and religious vocation plunge the viewer into a haunting illogic…a deeper mystery unnerving to today’s trends. Spiritual rootedness is hunted by the malaise of the times. The essentials of imagery, poetry, and prayer enable the second half of the performance to make vital incisions. It arrives at a liturgical poetry that strips away so as to welcome – and perhaps to release – an open silence at the core of self, memory, nation, and art.

REFLECTIONS

What is the role of art in a society ‘orphaned of transcendence’?[1] What happens to poetry when it is uprooted from its organic origins in religious ritual and sacred incantation? What happens to art when these ontological umbilical cords, linking it to the sphere of the sacred, and to the level of transcendence, are cut? What conditions their relationships to a society crafted in the image of deracination? What happens when retrieving symbol, metaphor, rhythm, from the chaotic chasm of language is no longer regarded alongside its ancient kindred, that is, the Stone Age extraction of flint from the earth, the dance of form with matter, of profane with sacred, of earth and hand, of eye and flint?[2]

Philosopher Jacques Maritain pondered the relationship between contemplatives and artists: ‘The Contemplative and the Artist, each perfected by an intellectual virtue which rivets him to the transcendental order, are naturally close. They also have the same brand of enemies. The Contemplative, who looks at the highest cause on which every being and activity depend, knows the place and the value of art, and understands the Artist. The Artist as such cannot judge the Contemplative, but he can divine his grandeur. If he truly loves beauty and if a moral vice does not hold his heart in a dazed condition, when his path crosses the Contemplative’s he will recognise love and beauty.’[3] One likeness uniting contemplative spirituality and the experience of art lies in its via negativa, its link with negation: an epistemology of sacramental openness. As Evagrius Ponticus, a fourth-century monk and ascetic, wrote: ‘prayer is the absence of concepts’.[4] Bernard Kelly, in the Twentieth Century recognised this: ‘We shall go no further without a certain mortification of the mind. Beauty is not a sensuous glamor, neither is it a logical descant upon things. It is not a link in the chain of discursion and rumination of which our mental life is largely composed, but has the character of originality, of freshness. It is not one of a train of concepts, but a reality at which we halt.’[5]

A glimmer of paradise, a meditative immersion, is one of the things at the heart of both prayer and experiencing works of art and poetry according to this way of looking. In a ‘momentary defenselessness in an abandonment to being’[6] the mind makes ‘a leap out of the derivative courses of the reason, and is aware of peril. It must make an act of faith in being, unprescribed by propositions; lay momentarily aside all its verbal certainties for the sake of a certainty deeper than concepts.’[7] This clearing, this incandescent castigation which breaks the captivities inherent in the endless cycle of propositions, dogmas, and merely verbal certainties, not to mention the epistemic cannibalism which is the stock in trade of many philosophers and scholars today, is both a point of contact between the religious person and the artist, and a point of discord and contention. For an artist subverts the traditional philosophical hierarchy which puts theology above ontology, and allocates philosophy the position of theology’s servant. An artist is an affirmation of a lived ontology of Mystery. Despite such differences both work against what Pope Francis has called ‘the degradation of awe’; and both work against the eclipse of the ontological mystery by a Western society captive to the forces of capital and technocratic hegemony.

CREDO

I write because of the cast iron frailty, the lead coffin vulnerability, which pulverises life. The sacred role of a poet is faithful transcription of intimate communion in solitude with humanity, nature, the sacred, and the self. The simultaneously penitential and festal receptivity of this form of listening and waiting requires a poet to stand paradoxically sentinel and prostrate in readiness to set ink on the page. As a poet I try to have my hands cupped for sacramental drops falling from the everyday chalice.

I reject everything that seeks to mutilate the solitude inhabited by writing and reflection. The vocation of the artist consists in not letting anything mutilate the eremitic rhythm – the pollinating cadaver of silence – in which reflection, seeking, and communions are born. ‘Not but in all removes I can / Kind love both give and get’, wrote Gerard Manley Hopkins. All acts of ontological closure are anathema to an artist. The artist is possessed by the flosculus intimations of immortality found in words staining – with bellicose tenderness – the world’s abysmally dressed wound.

So much of life is mauled by emptiness. So much is captivity to illusion or marred by the brutality of misperceptions. Language is lacerated in the torture chamber of technological hegemony. In the name of a fanatical secularism many are mercenaries maiming a sense of the sacred which is systematically exiled from society. On the other side, reflection on the abysmal failure of what has been called “Western Christianity” to dress the wounds of the world – in terms of its failure to humanise humanity, to even remotely resemble the movement of Christ and his Apostles, its collusion in the banishment of the sense of the sacred, its openness to being used as a battering ram in games of identity politics and conflict between classes etc. – might be enlightening. Almost everywhere someone dispenses the drugs of deracination. I reject all these séances at shrines of servility.

The mercenary spirit of today’s capitalist society is victim and perpetrator of the malaise of deracination. Its method derives from the rage of uprootedness. Speaking personally, it never tried to convince me of its right to exist, its goodness, or the value of its ideology. Instead it tries to maim one’s spirit and lead one into captivity. Rarely does it open a dialogue with the individual. When it does, this dialogue is accompanied by a barrage of discordant noise, that is, the whole mechanism of coercion by which is seeks to dominate the human soul. By ruthlessly intertwining consent and coercion, it demands consent in continual acts of attempted rape and attempted murder. My vocation as a human being, a poet, and an intellectual involves implacable hostility towards it.

What is an artist? A subversive psalmist of unknown cathedrals of negation – spaces in which the light of creative silence, thinking and questioning, still falls. Citadels of the spirit from which these acid efflorescences reach out into the world, returning once more to the solace of exile.

Poetry is a liminal requiem, a votive offering, caught between the waters of thought and the earth of language. Writers are the anarchistic priests of being. Their vocation is to be eremitic scribes of the ontology they perceive and which perceives them.

[1] Erik Varden, The Shattering of Loneliness, p30.

[2] In Britain BC archaeologist Francis Pryor comments on ‘the importance of ritual and ceremony in the winning of flint from deep in the ground’ (p155). I like to think of the poet’s craft as something like this: a poet descends into the amorphous and dark womb of earth and retrieves living material for shaping.

[3] Jacques Maritain, Art and Scholasticism, p83.

[4] The Praktikos and Chapters on Prayer, p66.

[5] A Catholic Mind Awake, p118.

[6] Ibid, p119.

[7] Ibid.

Excerpt from The Agony in the Garden

To celebrate the new year I offer this small excerpt from The Agony in the Garden, a brand new collection of poetry published via Wild Goat Press. It can be found here: https://www.amazon.co.uk/dp/1676540547/ref=sr_1_1?keywords=blake+everitt&qid=1578036517&s=books&sr=1-1

Stay tuned for more, including dates for upcoming recitals in support of The Agony in the Garden.

A MOMENT’S HARMONY

A moment shivers in silver rust

and Holy Miriam an amphora of glass

pours her wine on Vectis’s shores;

a still quarry of storm

to sheathe a hearth’s silence.

And a man must know

that land and sea

are older by far than Christianity.

Miriam’s icon in trees of glass.

Miriam’s cantor my Tree of glass.

As the discord paints a gold-sore’s grain

in a soul that is the stone-leaf’s clover

baked in red clay to dye the wine grey

and feel them run together in harmony.

WIGHT SPARKS

My word-spires rise in a chalice of quartz.

Your gifting island opens its eye

an Erebus melted in white stalks

to block the flint’s blue glare

knotted in the cull of finite rings

notches bled in the waxen kiss

of opal on ink: these my Wight sparks

grown here in obsidian ears.

Your word-spires spill flint

in the Wight chalice you offer.

IN THE SHADE OF A SAINT

I drink blonde ash

in the shade of a saint

whose forehead bears

an ulcer-crown.

I eat verdant bread

though its fire ignites my teeth

as bronze gallows fear ravenous gums.

I am all that’s left: I am Saint Boniface.

Pale bead of memory: I am Saint Boniface

drinking the light

in the soil-teat’s

cauldron of stars.

I drink blonde ash

in the shade of conquest:

my fingers are dirtied

with the slime of power.

Three Isle of Wight poems

The following three poems are from a forthcoming publication entitled The Agony in the Garden. These poems appear in section V of the book, subtitled Wight the Words You Gave Me.

WIGHT THE WORDS THEY GAVE ME

Wight the words they gave me;

stones spill over thrones of rain.

My light roams in the sky’s requiem

intoning brief flurries of algae

and the lime-laden hands of a ploughman’s cell

groping in shoals of grass-light

as a priest comes home for dawn

Wight the words you gave me

with the wild garlic’s song

where cliffs hatch plots – smuggle an older

layer (spirals of wine in circlets of bread)

as the land returns its own

in the cold dark straddling shape

that’s me showered in icy grain

peering from the doorway

fleeing the wind, though its light-goats ascend

higher and higher in joy’s requiem

dance of horn on horn and winter berries

bursting with salt from the seas down below.

Wight the words they gave me;

poor the lighthouse on Vectis’ shores.

Wight the words obeyed me

with the yellow hawk’s wand.

ST. CATHERINE’S ORATORY

In gold-shards the primeval Wight

glows with the morning star

green hems in mud flash

beside a trout’s lair

as clay beds down in soul

and St. Rhadegund’s blood foams from a well

ochre-black scarabs of advent flame

purring thorns gush from an island’s throat

throat-clouds of clotted glass

a liturgy in marble cast

at the foot of an Iron Age hut

on Gore Down’s green tips

eggs lashed by steam still coil

the baptised crofts of darkened days

as word-spawn breathes in voids of time

sowing then into now in primeval light

Chale’s white scarabs of Latin glass

blown in the furnace of Patmos

bright waters and sperm pyres blaze

in silver wombs of earth

the attracting eye’s primeval dance

where rivers ember their prayers for earth

and the wind cuts blade-swirls into grass

and a hermit lives an Elysium in God.

THE WORDFLOWER

Wordflower in razor sharp wind

secret bells cropped from chalice mouths

wordflowers gather in sunlight

singing verb-lizards nesting on rock

strophes of rainbow swords glistening

in mitres of seaweed rapt in cream light

yes the bluebells peel

green heads from my priests yes

grey knots of cloud

flow into nimbus-honey

stalks of yellow oak loveflames of sky and sea

anchoring in me a silence untouched

soil-waves sheer and silvery

the wordfish scales throw

black glints of drought

in my sky thawed by honey-sun rays

how many wordflowers cause this stain

how many wordflowers dye my liberty

how many wordflowers make up an island

TWO TEXAS POEMS

The following poems were written during a trip to Texas. Both, after returning to the Isle of Wight, found a home in Harbinger Asylum poetry magazine, based in Houston, TX.

THE PROPHET AMOS IN KATY, TEXAS

The withered top of Carmel

survives another flood

the shepherds cleave to rosary skies

hurled for Goliath’s repose

Amos your voice on the wind

travels for generations

provoked by mourning pastures

the dream cut with shards

from the Calvinist glass

a feasting robe denuded of skin

the seekers go astray

ash reclaiming its nothing

layers reliving their exile

launched with a tempest in the day of the whirlwind

sing, covenant of remembrance

sing, covenant of brotherhood

as fires devour the ribs of their living

this is your connivance with capital

Amos your voice on the wind

travels for generations

provoked by the mourning pastures

I keep in mind the cenobites

who watered seeds of wilderness

in a land plagued by “knowing”

as carts full of word-sheaves

weigh heavily on the broken string of affliction

as another empire’s language

creeps under the door.

ODE TO BORIS JOHNSON

Rachel has not gathered your tears, Boris

and you will have to answer to many broken lives

Rachel is out gathering tears, Donald

and the children of Amos hear shepherds weep.

The empire hews its stone, monstrance or sepulchre,

denying the faces of God.

Rachel has this to say to you:

only rivers of justice run free

and she merges skilled prudence with mercy

a child’s melody calling from the hills

we will reign

we are Reign

past the day of your lords

woe to those at ease in Zion

the monk-shepherds blessing

ringing out from Quarr.

Amos in Texas

The Prophet Amos in Katy, Texas

The withered top of Carmel

survives another flood

the shepherds cleave to rosary skies

hurled for Goliath’s repose

Amos your voice on the wind

travels for generations

provoked by mourning pastures

the dream cut with shards

from the Calvinist glass

a feasting robe denuded of skin

the seekers go astray

ash reclaiming its nothing

layers reliving their exile

launched with a tempest in the day of the whirlwind

sing, covenant of remembrance

sing, covenant of brotherhood

as fires devour the ribs of their living

this is your connivance with capital

Amos your voice on the wind

travels for generations

provoked by the mourning pastures

I keep in mind the cenobites

who watered seeds of wilderness

in a land plagued by “knowing”

as carts full of word-sheaves

weigh heavily on the broken string of affliction

as another empire’s language

creeps under the door.

In the prophet Amos I count eight essential, but not exhaustive, themes: (1) warnings against merely ritual religion, (2) warnings against indifference to injustice, (3) warnings against opulence at the expense of the poor and the land, (4) the dehumanising touch of lucre in human life, (5) the role of prophets in the collective, (6) God’s implacable hostility towards capitalism (profiteering and commodification of all things), (7) the ascesis of the prophet’s oppositional vocation, (8) divine wrath against human arrogance and the architecture of arrogance.

The voice of Amos echoes the fearless freedom of the wind, striking hammer blows of the Spirit today. ‘Thus saith the Lord; For three transgressions of Israel, and for four, I will not turn away the punishment thereof; because they sold the righteous for silver, and the poor for a pair of shoes; That pant after the dust of the earth on the head of the poor, and turn aside the way of the meek’ (Amos 2:6-7). The structural injustice of capitalism today receives a stark warning from the Judaeo-Christian God. Today’s structures still sell the righteous for silver and the poor for gain. The poetic realism of Amos is a prophetic torch on collision course with the dynamic of dominion, to use a phrase from Pope Francis, which dominates society today. ‘And he that is courageous among the mighty shall flee away naked in that day, saith the Lord’ (Amos 2:16). The heads of state, military leaders, CEO’s of global corporations, the vultures of financial idolatry – all will be stripped of the vestments of vapidity they flaunt and store.

One is confronted today by the entire theological arsenal of capitalism. It amounts to the ossification of injustice, where humanity is divided by those who ‘oppress the poor, who crush the needy’ (Amos 4:1). Instead, we are called to witness a vivifying, revolutionary metanoia: ‘For thus saith the Lord unto the house of Israel, Seek ye me, and ye shall live’ (Amos 5:4). Against the seductive voice of economic doceticism (which whispers that one’s financial prosperity and its ersatz theology of lucre is entirely distinct from one’s liturgical and ethical actions) we must sanctify our lives – and the lives of our sisters and brothers – with true love of the Incarnation.

I believe it is a mistake to think of today’s society as atheist. It has its gods, before which it prostrates itself: profit, careerism, commodification, consumerism, money. It is neither atheistic in word nor in practice. The type of skilled and calculated motivation many demonstrate does not come from indifference, disbelief, or confusion. It comes from the deep seated piety of economic theology: the theology of filthy lucre. It is a system seeking to turn each individual – the more easily to coerce us – into those ‘who turn justice to wormwood, and lay righteousness to rest in the earth’ (Amos 5:7). Amos draws a stark portrait of such a coerced and captive population: ‘They hate him that rebuketh in the gate, and they abhor him that speaketh uprightly. Forasmuch therefore as your treading is upon the poor, and ye take from him burdens of wheat: ye have built houses of hewn stone, but ye shall not dwell in them; ye have planted pleasant vineyards, but ye shall not drink wine of them. For I know your manifold transgressions and your mighty sins: they afflict the just, they take a bribe, and they turn aside the poor in the gate from their right’ (Amos 5:10-12). Amos excoriates elements of systematic sin: denial of free and open speech, forcible extraction of taxes, the institute of private property, the incarceration and murder of many martyrs of justice and the Reign, and indifference to the plight of the impoverished.

The prophet asks each one of us directly: is your faith merely ritualistic or does it fully take into account the Gospel’s precious flower of justice? Does your liturgical activity truly integrate itself with the ongoing Passover it requires of your whole being? Does it transcend an exclusively ritualistic and disembodied note of piety without radical fidelity to the Beatitudes and Maledictions? ‘I hate, I despise your feast days, and I will not smell in your solemn assemblies. Though ye offer me burnt offerings and your meat offerings, I will not accept them: neither will I regard the peace offerings of your fat beasts. Take thou away from me the noise of thy songs; for I will not hear the melody of thy viols. But let judgment run down as waters, and righteousness as a mighty stream’ (Amos 5:21-24).

The prophetic sword seeks to cleave even the shadow of hypocrisy, and the distress of dis-incarnation, in two: ‘Woe to them that are at ease in Zion, and trust in the mountain of Samaria’ (Amos 6:1). Ease, indifference, self-seeking, spiritual careerism, empty moralism, faith without works, and faith without radical challenges to the class conflict created by capitalism – all are questioned by Amos.

‘Hear this, O ye that swallow up the needy, even to make the poor of the land to fail, Saying, When will the new moon be gone, that we may sell corn? and the sabbath, that we may set forth wheat, making the ephah small, and the shekel great, and falsifying the balances by deceit? That we may buy the poor for silver, and the needy for a pair of shoes; yea, and sell the refuse of the wheat? The Lord hath sworn by the excellency of Jacob, Surely I will never forget any of their works. Shall not the land tremble for this, and every one mourn that dwelleth therein? and it shall rise up wholly as a flood; and it shall be cast out and drowned, as by the flood of Egypt’ (Amos 8:4-8). One is confronted by theory and practice which constitutes a rhythm antonymic to the aim of Christian life: antonymic to soteriopraxis, and inimical to the incisive action of Scripture: ‘For the word of God is quick, and powerful, and sharper than any twoedged sword, piercing even to the dividing asunder of soul and spirit, and of the joints and marrow, and is a discerner of the thoughts and intents of the heart’ (Hebrews 4:12). And to the Incarnation itself. Ours must be an incarnational antonymicide, rooted in the mercy and love shown humanity in the Incarnation. Saint Athanasius sings hymns of metaphysical realism to the tenderness of the Incarnate Word: ‘having mercy upon our race, and having pity upon our weakness, and condescending to our corruption, and not enduring the dominion of death, lest what had been created should perish and the work of the Father himself for human beings should be in vain, he takes for himself a body and that not foreign to our own’ (On the Incarnation, p57).

Capitalism has its “damned” and its “elect”. It drinks from the well of secularised (or polytheistic) Calvinism. It has its egocentric and immature puritanism (the puritanism of the market!). Many today forget the words of poet Geoffrey Hill: ‘in the half dark of commodity most offers are impositions’. Let us not be guilty of this amnesia. Our examination of conscience and practice should ask the question, are we children of the prophets or children of profiteers?

In such a climate the Christian task – the apostolic charism of all Christians – is to be neither one of capitalism’s “elect” nor one of its “damned”. Both imply captivity, and Christ came to lead captivity captive. Let ours be a soteriopraxis of subversion set ablaze by the fiery sacrament liberty (paschal torch so loved by the apostles!), renouncing and denouncing the laws of filthy lucre. Let ours be the bellipotent[1] tenderness of the Beatitudes, reciting with Amos the lyrics of mystery and vocation: ‘I was no prophet, neither was I a prophet’s son; but I was an herdsman, and a gatherer of sycamore fruit’ (Amos 7:14).

[1] Recorded in Samuel Johnson’s 1735 Dictionary with the meaning of ‘mighty in war’.

Poems from South-West France

1. AT LOURDES

Bernadette,

ascesis of anguish,

your wooden shoes

carved the sacred tree

how many waters of sound part the silence?

Knives of stone clarity

jagged prayer of watchful hills

battered Reign, we beg, do not abandon us

to the ascetic night of spiders

drawn in silver webs of grace

flowing outward, beyond

as pain recoils

from love

a last time

saint of severed bone

fingers worn in rosary stream

stations on the way of liberation

we share in the banquet of the broken

2. AT THE CHURCH OF SAINT QUITERIA IN AIRE-SUR-L’ADORE

To live this day

in folds of martyring night

where blood loves its soil

spent in the winepress’ brisk rage

your grave to call us home

withering sheen of another’s tomb

your credo white, a poetry of wildflowers,

the lilies’ longing raw: go out in green

sacramental, free, and carve the stone

you would have call you its home

red words engrafted white

down the stairs of Saint Quiteria’s flight

where silence heals beheadings

and doves bury your sister

the way moss psalms its sorrow bright

aspiring to name colours of ancient loves

in the crypt a sarcophagus stays

a hesychia anointing each day

3. AT THE CRYPT OF SAINT GIRONS

Saint Girons the martyr’s claw

churns the soil fertile and raw

as the Abbey’s outline plays its tune

and Charlemagne’s moon secures its pitch

adoring plainchant of lily and land

cupped for wine in evangelists hands.

Will I go down the stair unknown

to rise prostrate in martyr’s groves

and will you retrieve the Word-sewn flesh

pining light pure in personified rest?

Saint Girons the bark still gnaws

cut from trees obscuring shores

as the chapel’s outline plays its tune

4. AT THE BIRTHPLACE OF SAINT VINCENT DE PAUL

The bells caress Our Lady of Buglose.

Ink filled with Pentecostal glow

baptising the paper on which I write

dry bones ignite

the rain’s incensing wind

small Passover storms

dissolving the riddle of self.

Relics call the fever of dawn

ascesis of light

where faith gnaws its cloth

in the shape of Christ.

Palms of the Way

waters of shade

in prayer-spray’s Reign

I will go and die with him

lighting my loneliness

with Easter’s presence

burning the silence with flames kindled

by knees bent in love

arc of sternum drizzled in blood

fingers crying the severed night

as bells caress Our Lady of Buglose.

(poems from Wildflower Psalms out now via Wild Goat Press)